Dear Benedict,

After a week of Covid19, I’m gradually feeling better: tiredness continues. What with other folks I know also testing positive it made me think a bit differently about Holy Week.

It’s hard enough being holy for a week without being wholly weak. But every week includes weakness. You allowed for Alleluias ‘except in Lent’ (chapter 15) and evidently that meant you were more generous with this practice than some instructors. So I’ll just fit in a quick Alleluia for weakness while I’m here.

It’s hard to celebrate weakness in a culture that hard on the soft aspects of being human. Even in this week of weeks the bits that could be seen as weak are edited to distance us from too much weakness.

A man arrived at the city gate on a donkey, like many did every week. Rather than see this as ordinary, let alone weak, a great cheering crowd is heard making a fuss about a king coming, however unlikely the beast. Some say the donkey knew: they are knowing creatures.

Tired, weary and as weak as you or me, Jesus climbs off the donkey and disappears into the underbelly of Jerusalem. When he reappears he’s sitting down, not standing, in the temple. Just watching, just waiting, just breathing, he notices ordinary things. There’s an ordinary woman who makes an ordinary offering. Easy to overlook that.

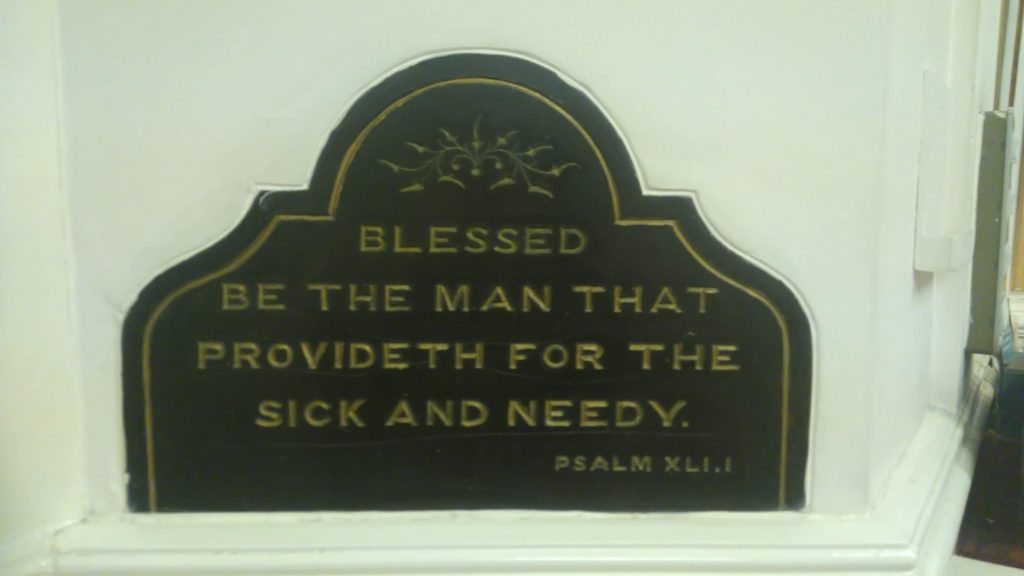

Easy to overlook the poor today even though they are still with us. To overlook the ones on pre-payment meters queuing at local foodbanks for food that doesn’t need cooking. The message seems to be weakness should be ignored. But not by Jesus who remarks that it’s ‘All she had to live on’. It’s still up to us to determine if it’s enough to provide pot noodles or whether we should entice anyone into making a greater fuss alongside the weak.

It’s a week in which weakness continued to surface in all kinds of ways. Coming to the end of his temper with things as they were: a fig tree with no fruit, a temple market place with no justice, who wouldn’t loose it, and let it loose to echo down history as weakness or what? I’ll add a quick Alleluia for that too.

In a weak moment he takes the towel and tries to show them what it’s really like being part of a squabbling community in a place of political turmoil. Alleluia for clean feet.

In a weak moment he takes bread, ordinary stuff, and tries to say something about the yeast infused stuff that feeds them and the fermented juice that runs in their veins over hundreds of years of running away. They miss a lot of it, as do we, unhappy about too much weakness. We squabble about who was and who wasn’t there, what was and wasn’t said, what it did or didn’t mean, instead of taking the stuff and sharing it. ‘This is my body’: Alleluia for that.

The Mount of Olives at night would have been a dark and isolated place. Not a place for sleeping or for lover’s to meet and kiss. Giving all his strength away, as he has been throughout his ministry, he is taken away in weakness. Alleluia for that.

From there on, everything tumbles away until stripped and bleeding, nailed and tormented, all that’s left is weakness. And perhaps that why we want to edit the weak bits, busy concentrating on getting the right ending rather than what it takes to get there. Who wants a weak leader, one with mental health challenges or physical limitations, a mistake-maker, giver-upper? No mask or put on face here. Only the agonised admission: it is finished. Alleluia for that.

My week will have weak bits, tired bits, uncertain and unconvincing bits. The answer will be ‘I don’t know’ several times a day. I’ll step away, avert my eyes, deny and prevaricate. And from time to time, I may just glimpse some holiness in all this and raise my feeble Alleluia.

From my remembered bible: There was silence

Alleluia!

From a Friend of Scholastica and a Member of the Lay community of St Benedict.